I follow my old landlady to the edge of the culvert. She points down to the murky water below. "Several years ago this was a dump. Plastic bags and shopping submerged in a water covered with oil slicks. Then the city came and tried to clean it up. They pumped the water out, planted reeds along the stream and put up a fence to keep people out. It looked really good for a few months. Now after all that work, the water is as dark and murky as it was before."

When I lived at her house, I used to come jogging through the Mystic River Reservation—seeing the reeds, the vista of the river, the graffiti carved into the wooden observation tower, the cracks on the asphalt path. But, as we walk through the park she points out elements and changes which I, at a jogger's pace, never had time or reason to notice. Just as at a jogger's pace I notice things about the city which are invisible to driver of an automobile. At a curve on the asphalt path, we follow a trace where the grass has been worn down—into the brush where we come upon the thickets of blackberries, the objective which was brought her, as it has for years, to walk slowly along the edge of the Mystic River, watching how its banks have changed through the years.

I was a transportation planner, I designed traffic intersections based on a bunch of numbers from a single days observation, and occasionally got shouted at by people who had to wait at the stop light every day. And it is sad to think that the professionals brought in to reclaim the stream in a manic burst, may not understand the factors affecting it. And of course so much of our system is designed from the perspective of the automobile, not the bicyclist or the walker, let alone the blackberry forager.

This is a good year for blackberries, and we easily fill our containers—discussing, as we have before, whether money is a fundamentally corrosive influence on society, and parting ways on the issue of whether it is a compliment to say of some one that they can run a business at a profit.

Years ago in Los Angeles, I was walking with a friend from college who works for the Long Beach Fire Department. As we walk through the city, he points out the roofs, what they imply for the way fire will spread through a building. He talks about how he was trained to analyze them, through books, and instruction, and the way his colleagues sometimes hide on the roof of the fire station, pouring water on recruits who haven't learned to Always look up, before entering a building. Later, at home, he shows me snapshots from fighting a wildfire. All of these objectives: fighting fires, picking blackberries, driving motorcars shape what we do notice about our surroundings, and what we should notice about them. A deer hunter walking through the woods will be attuned to different elements among the tree bark, or the trail floor than a forester or a fire fighter

In 1984 Winston Smith encounters an old workingman in a bar, and attempts to find out the definitive reality the propaganda people like himself are employed to write. "Has the Revolution made your life better...yes or no?" The old man, quite sensibly for some one talking to a stranger in a police state, never gives a straight answer to any of his questions—though he does offer an unsolicited opinion on the difficulties of drinking litres instead of pints (and then forgoes his principles for the sake of free beer).

Years ago I stayed with a family in a shantytown in Managua: plastic sheeting for walls, but lots of stuffed animals, and a TV where they could watch the wrestling. The father had fought for the Sandinista Government against US proxies. But now his comment was "You know, Somoza, the Sandinistas, Aleman—the price of tomatoes just keeps going up." As some one who grew up with a reverence for the Sandinistas and their revolution, it was a disheartening comment to hear.

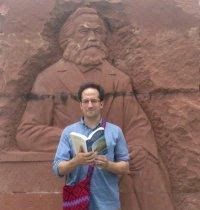

"All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind." Maybe there is no objective perspective, no universally apparent conditions of life, just the comments about the metric system we can make based on years of working at our trade, or picking blackberries along the Mystic.

Friday 22 August 2008

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)